How To Sue An Oil Company (from The Washington Post)

Posted by keith on May 24th, 2010

I have very little faith in any of the instruments of civilised society; but when you are faced with something like the BP Deepwater Oil Tide™ then a combination of both civilised and uncivilised activities may well be the best course of action – if only to allow one to mask the other…

How to sue an oil company: Tips for the gulf from a veteran of the Valdez spill

By Brian O’Neill

Sunday, May 16, 2010

For 21 years, my legal career was focused on a single episode of bad driving: In March 1989, captain Joseph Hazelwood ran the Exxon Valdez aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound.

As an attorney for 32,000 Alaskan fishermen and natives, I tried the initial case in 1994. My colleagues and I took testimony from more than 1,000 people, looked at 10 million pages of Exxon documents, argued 1,000 motions and went through 20 appeals. Along the way, I learned some things that might come in handy for the people of the Gulf Coast who are now dealing with BP and the ongoing oil spill.

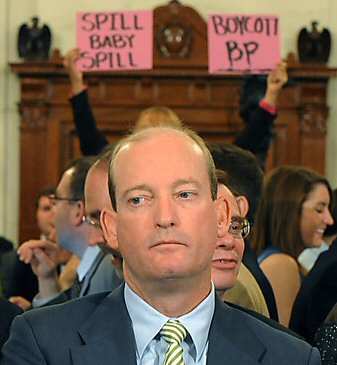

Brace for the PR blitz

BP’s public relations campaign is well underway. “This wasn’t our accident,” chief executive Tony Hayward told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos earlier this month. Though he accepted responsibility for cleaning up the spill, Hayward emphasized that “this was a drilling rig operated by another company.”

Communities destroyed by oil spills have heard this kind of thing before. In 1989, Exxon executive Don Cornett told residents of Cordova, Alaska: “You have had some good luck, and you don’t realize it. You have Exxon, and we do business straight. We will consider whatever it takes to keep you whole.” Cornett’s straight-shooting company proceeded to fight paying damages for nearly 20 years. In 2008, it succeeded — the Supreme Court cut punitive damages from $2.5 billion to $500 million.

As the spill progressed, Exxon treated the cleanup like a public relations event. At the crisis center in Valdez, company officials urged the deployment of “bright and yellow” cleanup equipment to avoid a “public relations nightmare.” “I don’t care so much whether [the equipment is] working or not,” an Exxon executive exhorted other company executives on an audiotape our plaintiffs cited before the Supreme Court. “I don’t care if it picks up two gallons a week.”

Even as the spill’s long-term impact on beaches, herring, whales, sea otters and other wildlife became apparent, Exxon used its scientists to run a counteroffensive, claiming that the spill had no negative long-term effects on anything. This type of propaganda offensive can go on for years, and the danger is that the public and the courts will eventually buy it. State and local governments and fishermen’s groups on the Gulf Coast will need reputable scientists to study the spill’s effects, and must work tirelessly to get the truth out.

Remember: When the spiller declares victory over the oil, it’s time to raise hell.

Don’t settle too early

If gulf communities settle too soon, they’ll be paid inadequate damages for injuries they don’t even know they have yet.

It’s difficult to predict how spilled oil will affect fish and wildlife. Dead birds are easy to count, but oil can destroy entire fisheries over time. In the Valdez case, Exxon set up a claims office right after the spill to pay fishermen part of their lost revenue. They were required to sign documents limiting their rights to future damages.

Those who did were shortsighted. In Alaska, fishermen didn’t fish for as many as three years after the Valdez spill. Their boats lost value. The price of fish from oiled areas plummeted. Prince William Sound’s herring have never recovered. South-central Alaska was devastated.

In the gulf, where hundreds of thousands of gallons of crude are pouring into once-productive fishing waters every day, fishing communities should be wary of taking the quick cash. The full harm to their industry will not be understood for years.

Hire patient lawyers

After the Valdez spill, 62 law firms filed suit against Exxon. Many lawyers thought they would score an easy payday when the company settled quickly.

They were wrong. My clients resolved their last issue with Exxon just last month. The coalition of firms that stayed with the case expended $200 million in billable hours and $30 million in expenses. Exxon began paying compensation to lawyers only two years ago. In the end, we were able to recover about a fourth of losses suffered by fishermen and natives.

And no matter how outrageously spillers behave in court, trials are always risky.

Though an Alaska criminal jury did not find Hazelwood guilty of drunken driving, in our civil case, we revisited the issue. The Supreme Court noted that, according to witnesses, before “the Valdez left port on the night of the disaster, Hazelwood downed at least five double vodkas in the waterfront bars of Valdez, an intake of about 15 ounces of 80-proof alcohol, enough ‘that a non-alcoholic would have passed out.’ ” Exxon claimed that an obviously drunken skipper wasn’t drunk; but if he was, that Exxon didn’t know he had a history of drinking; but if Exxon did know, that the company monitored him; and anyway, that the company didn’t really hurt anyone.

In addition, Exxon hired experts to say that oil had no adverse effect on fish. They claimed that some of the oil onshore was from earlier earthquakes. Lawrence Rawl, chief executive of Exxon at the time of the spill, had testified during Senate hearings that the company would not blame the Coast Guard for the Valdez’s grounding. On the stand, he reversed himself and implied that the Coast Guard was responsible. (When I played the tape of his Senate testimony on cross examination, the only question I had was: “Is that you?”)

Keep hope alive*

Historically, U.S. courts have favored oil spillers over those they hurt. Petroleum companies play down the size of their spills and have the time and resources to chip away at damages sought by hard-working people with less money. And compensation won’t mend a broken community. Go into a bar in south-central Alaska — it’s as if the Valdez spill happened last week.

Still, when I sued BP in 1991 after a relatively small spill in Glacier Bay, the company responsibly compensated the fishermen of Cook Inlet, Alaska. After a one-month trial, BP paid the community $51 million. From spill to settlement, the case took four years to resolve.

Culturally, BP seemed an entirely different creature than Exxon. I do not know whether the BP that is responding to the disaster in the gulf is the BP I dealt with in 1991, or whether it will adopt the Exxon approach. For the sake of everyone involved, I hope it is the former.

* And just for the record, I don’t believe in hope: when all you are left with is hope, do something better!