Libraries gave us power

Then work came and made us free

But what price now for a shallow piece of dignity

– A Design for Life, Manic Street Preachers

Could these be the most ironic lines ever written, or just a dumb piece of worthy lyricism?

Take them apart and any scholar of European history will see the translation of the second line etched in their mind and still remaining above the gates of Auschwitz: Arbeit Macht Frei. If work made us free then the Caribbean and Deep South slaves must have experienced a rare level of freedom, only now being reclaimed in the sweatshops of China and India. I suspect, though, Nicky Wire didn’t write the second line in complete naivité…

But it is the first line I take real issue with; for while the knowledge gained during the free gathering of information in the libraries of South Wales – which inspired the lyric “Libraries gave us power” – may have allowed many people to take work opportunities in areas they may not have previously considered, or been able to, there is little chance of a person reading the texts available to them differentiating what is relatively balanced from what is explicit cultural-brainwashing.

Nowhere does this brainwashing exist more than in the definitions handed out by dictionaries.

“You know some may not like to hear it, but history is not on the side of those who manipulate the meaning of words like revolution, freedom, and peace.”

– Ronald Reagan, Hambach, West Germany, 1985.

You want to put money on that, Mr Reagan? The history of conflict, suppression and imperialism shows that language is one of the key weapons in the arsenal of anyone that wishes to take control of a population. I took this subject on in a recent Earth Blog article:

Words are enormously powerful; in many ways they are a defining feature of our culture, not only because of the number of ways that they can be used – in the form of poetry, debate, story-telling, song and innumerable others – but also because we have become conditioned to accept certain words as having significance beyond their physical incarnation. These words are more than just symbols – they are tools that can be, and are, used to manipulate the way we think and act.

“They behaved like animals!”

The use of the word “animal” in that context is not accidental; it derives from the Enlightenment view that humans were above the common animal whose screams were “the mere clatter of gears and mechanisms”. Despite us clearly being animals, the adopted viewpoint is that to behave like an animal is to be less than human. Is this your viewpoint, or were you taught to think like that?

It is some small relief that the German philosopher, Wittgenstein took the view that our internal experiences were isolated from what we would normally understand as language. He explained this in the context of pain, in that a person could reasonably question (through our use of language) whether we were in pain or not; but we could never doubt whether we are in pain or not – the experience is not subject to communicating that experience. This suggests that our internal self is isolated from the outside world by the lack of a useful interface, thus providing us with some protection from cultural interference.

Nevertheless, as we strive to communicate our experiences through words (among other things) such that others may understand them, we open up a door to these experiences, and in doing so allow a dialogue to exist. The interface between our internal experience and the external manifestation of these experiences is not a one way street. Words affect our emotions, they can hurt, they can heal, they can change who we are.

“I hate you!”

“I love you.”

Why do politicians make speeches? One could make the argument that they simply like the sound of their own voices, but in that case why not just talk to an empty room? The point is that politicians understand the nature of this interface between the external and the internal only too well. Rhetoric can sway opinion; true oratory can create lifelong beliefs: once more unto the breach brothers and sisters, fight them on the beaches and be the change you want to see.

Just words, surely?

No, not just words – ideas enshrined in policy and broadcast through the mouths of the common man, the paid-up celebrity and the pages of your children’s schoolbooks. Orwellian speak seems quaint and almost harmless compared to the ideas we are being asked to swallow – from the joys of wage slavery to the wonders of the infinite growth economy, via the imposition of “freedom” through the barrel of a gun. If you can dress it up in the right words then people will accept almost anything.

As part of my attempt to redress the balance, in favour of language that provides a more objective view of the world, I suggested that we start defining certain key words in terms of their predefinitions; in short, it is imperative – in a culture that succeeds to suppress any vestiges of true thought-freedom – that we use words in a way that benefit humanity rather than the systems that control humanity. We need to reclaim these words for ourselves.

But it is not just definitions that matter. In a society where there are scarce opportunities to present more accurate definitions of the words we use, we need to utilise a variety of means in this difficult struggle to free peoples’ minds from the tyranny of the civilised lexicon. What follows is a range of tasks, some of which everyone will be able to take part in; some of which are more challenging, but all of immense value in the war of words that must begin…

No Risk / Low Risk

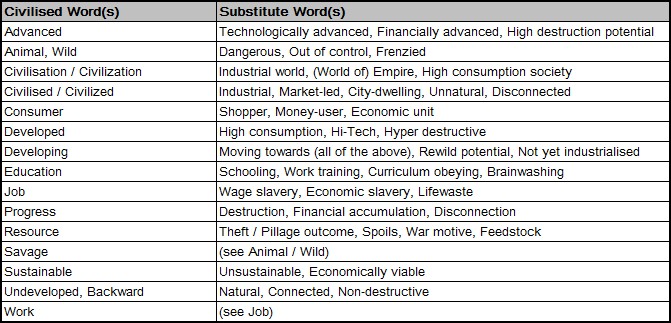

The key action in this category is Word Substitution and Predefinition, with Substitution probably being the more effective in the short term. As described in the Earth Blog article (linked above) there are a fairly large number of words that have been changed by civilised society in order to effect cultural change among the general population, the definitions of which we have learnt to accept as the norm. All of these words have a Predefinition, which I would ask you to become conversant with, so that you can decide whether your use of a word in normal conversation and writing is appropriate. If you ever have the opportunity to discuss their definitions – perhaps you could write a blog or three about these words – then do so.

But because of the extent to which their meanings have been changed, what happens is that simply using these words in their civilised context acts to reinforce their civilised meanings. If you are having a conversation with or writing an email or letter to someone who has no idea of the difference between the civilised world and the uncivilised world, then your words will automatically be taken with their civilised (a.k.a. conventional) meaning. Therefore, all of the words need some form of Substitution that can be used when communicating with a civilised person.

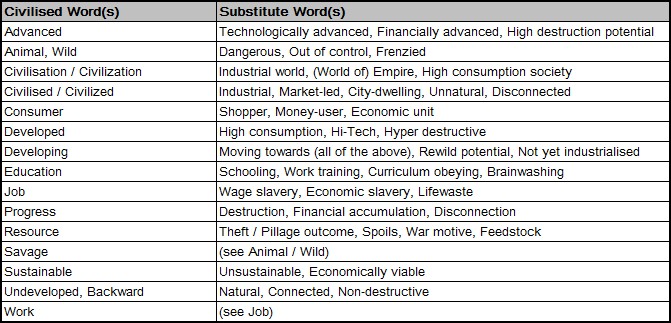

The table below gives suggestions for each Civilised Word – they are not all exactly synonymous, but should provide sufficient scope for normal communication:

Related to this is something more subtle, but potentially even more powerful: that is the adoption of E-Prime in your communication. I became aware of this whilst reading “Rewild or Die” by Urban Scout, where I discovered, to my astonishment, that the entire book had been written without the verb “to be”. Scout goes on to explain some of the rationale behind using such a way of communicating:

Our linguistic world eats itself and arguments ensue. “To be” prevents us from experiencing a shared reality; something we need in order to communicate in a sane way. If someone sees something completely different than another, our language prevents us from acknowledging the others point of view by limiting our perception to fixed states. For example, if I say “Star Wars is a shitty movie,” and my friend says, “Star Wars is not a shitty movie!” We have no shared reality, for in our language, truth lies in only one of our statements and we can forever argue these truths until one of us writes a book and has more authority than the other. If on the other hand I say, “I hated Star Wars,” I state my opinion as observed through my own senses. I state a more accurate reality by not claiming that Star Wars “is” anything, as it could “be” anything to anyone. Similarly one could say, “I’ve seen Urban Scout act like an idiot before,” while another person could say, “Man, Urban Scout has really made me think. I really appreciate him.” We have two perceptions that do not contradict one another, but came about from different perspectives.

“To Be” plays god. It attempts to chisel reality in stone and works as the backbone of the civilized paradigm. Of course it does, its birthplace lies in the land of economic commerce, not a biological community. English works to domesticate the world as much as tilling means to domesticate it. Every element of our culture urges for domestication, for slavery. If language shapes how we perceive the world, nothing stands more fundamental (aside from the practice of agriculture itself) to this process of domestication than our own language.

You will see that, apart from the quoted sections, those two paragraphs do not contain the offending verb at all; and notice how much more deliberate and less confrontational the words come across. Not that everyone will find it easy to communicate in a way that omits such a fundamental piece of such a widely adopted language, but I have managed it in this paragraph, and it does feel rather good – wholesome even. You could go further and explore an even more naturalised form of English (if you speak that language) – E-Primitive – which Willem Larsen has written about in this piece (see link); again, exceptionally difficult for someone deeply encultured by civilization, but a fascinating concept.

Now, I have no experience of the impact such a way of speaking is likely to have in practice and it may be that simply eliminating the verb “to be” will be nothing more than a talking point – nevertheless, even as a talking point it raises important issues about the nature of our relationships with the rest of nature and between each other; and it may trigger a change in the nature of these relationships…

Medium Risk

Now we have the basic tools for undermining the civilised theft of language (and don’t forget, there is no reason such activities should be limited to English – I just don’t have the linguistic capabilities to take this on) we need to explore a range of different environments in which they can be used.

As a method of Undermining, the aim of this task is to tip the balance back towards natural, uncivilised language; therefore it is not just a case of taking a neutral viewpoint, but instead using words and word structures in the opposite sense to that desired by the civilised world. This is where the risk comes in for those in a professional capacity, for if you are in one of the roles that can potentially change attitudes in this area – such as a journalist, teacher, broadcaster or politician (ok, maybe not a politician) – then you are also subject to a range of highly oppressive social norms: you have to speak, write and behave in a certain way. Step outside of these norms and you risk your position and, more importantly, your potential to be influential.

I do understand that this may seem a controversial position to take, but I take the view that if we didn’t have the problems we currently face, then we wouldn’t need to use the methods that are often necessary. A teacher or journalist can use their, albeit civilised, position to make a real difference – at least while they are permitted to. If you hold a position of influence with regards to the way people use language, then your act of using “civilised” in a negative sense, or your refusal to describe a frenzied attack as “wild” or “savage” is a powerful act indeed.

There are all sorts of actions possible besides merely speaking one-to-one – here are a few suggestions, which I will be delighted to add to should anyone suggest them to me:

Teach in E-Prime: Very tricky without practice or a lesson script, but then you could tell your students that you are doing it, why you are doing it, and ask them to help out with the “experiment”. Don’t forget to involve your trusted colleagues in your “experiment” too.

Read the news, substituting natural words for those in the script: How far you can get away with this depends on the nature of the reports, but maybe no-one will even notice, except subconsciously.

Write articles that turn word meanings around: This will almost certainly go against the editorial policy you are subject to, but you could always claim you slipped up when referring to workers as “wage slaves” or consumers as “economic units”.

Refuse to follow any script that uses civilised meanings or conventions: When I was a McDonalds wage slave, in the early 1990s, I refused to say, “How may I help you Sir / Madam”. Firstly, I objected to using the submissive personal title; secondly, I substituted “may” with “can”, as I explained that anyone coming into the place obviously wanted to buy something! Needless to say I was taken off till work, but it was quite enjoyable while it lasted.

Make editorial changes to articles or news: If you are a sub-editor for a small newspaper or magazine – you are much more likely to avoid editorial oversight with small titles – then you will have considerable licence to edit down and change submitted pieces in an uncivilised way. A good editor could get away with stripping out every pro-civilization word without being noticed; a really good editor can tip the balance the other way…

While the sword may be mightier than the pen when face-to-face in a duel, there is an awful lot you can change simply by minding your language. And what could be more empowering than wresting control from the machine of the words that are rightfully yours to use how you see fit?