Animal Eating “Vegetarians” On The Rise?

Posted by keith on November 5th, 2009

I really shouldn’t have to justify my diet — I don’t eat meat, eat a bit of dairy and a few eggs and have a ravenous taste for vegetables of all sorts. In short, I’m a typical healthy adult vegetarian; not a vegan, not a fruitarian, and certainly not a “pescetarian”. The last one is where it starts getting silly, because as far as I, the Vegetarian Society and Viva are concerned, if you eat fish then you aren’t a vegetarian of any sort, regardless of your reasons for eating it.

In terms of ethical hypocrisy, there are few things that sit more solidly in the realm of ethics than the decision over whether to kill something for food. If you buy a processed microwaveable beef lasagna from a supermarket, you are still responsible for the cow’s death — you can’t get away from it. What you eat is your choice, unless it imposes seriously upon others; but if you call yourself a “vegetarian” when you still eat fish, or chicken (yes, people do) then you are are being a hypocrite, and also making life a bit more difficult for real vegetarians.

Here’s an excellent story from the BBC News website, which makes all of this crystal clear.

The conversation usually goes something a bit like this:

“Yeah, I’m a vegetarian.”

“But that looks like fish you’re eating.”

“Oh yeah, I eat fish.”

Confusion, perplexity and occasionally heated debate can follow as the “vegetarian” and their interrogator cover the issue of what is an animal and whether fish feel pain. But the Vegetarian Society, which has acted as the custodian of British vegetarianism since 1847, has a simple definition.

“A vegetarian does not eat any meat, poultry, game, fish, shellfish or crustacean, or slaughter byproducts,” it says. They can make that even more pithy: “We don’t eat dead things.”

The society tackles the issue of fish-eating vegetarians with a page headed in red capitals: “VEGETARIANS DO NOT EAT FISH.”

Juliet Gellatley, director of the vegan and vegetarian group Viva, is also clear on the issue of whether fish eaters can use the term vegetarian.

“They cannot. The definition is very clear. It’s someone who doesn’t eat anything from a killed animal.

“It does cause confusion if someone who calls themselves a vegetarian goes into a restaurant and orders a prawn cocktail.”

Many of the fish-eating vegetarians will be making a dietary exception for health reasons. The government advises the consumption of at least two portions of fish a week, one of which should be oily fish. This intake is thought to help fight heart disease. Vegetarian organisations have to counter by noting that some nutritional benefits of eating oily fish can be gained from elsewhere. They recommend things like flaxseed oil and walnuts.

VARIANTS

Classic vegetarian: Eats no part of any dead animal

Vegan: Eats no animal product

Meat-avoider: Tries not to to eat meat but has occasional lapses

Meat-reducer: Is trying to eat less meat, probably for health reasons

Green eater: Avoids meat because of environmental impact

There may also be a tendency among some fish-eating vegetarians to assign a different ethical equation to the consumption of fish. It is something that is vehemently rejected by vegetarians.

“There is ample evidence in peer-reviewed scientific journals that mammals experience not just pain, but also mental suffering including fear, anticipation, foreboding, anxiety, stress, terror and trauma,” says Revd Prof Andrew Linzey, director of the Oxford Centre for Animal Ethics and author of Why Animal Suffering Matters.

“The case for fish isn’t so strong, but scientific evidence at least shows that they experience pain and fear. Anyone who wants to avoid causing pain should give up eating fish.”

But there is a wider problem of identification.

“Fish don’t invoke the same compassionate response that a calf, lamb, piglet, or duck does,” says Ms Gellatley. “We are mammals, we relate much better to other mammals. When we see a pig in a factory farm and you can see that animal is in pain that has a very direct effect on people.”

Vegetarian escalator

And then there’s the issue of depleted fish stocks.

Fish-eating vegetarians used to have their own term – “pescetarian” – although it seems not to be in common use today. But, Ms Gellatley says, there is a rise in the use of a new term for the part-vegetarian.

“The name ‘flexitarian’ is coming into use. It’s fairly meaningless really.”

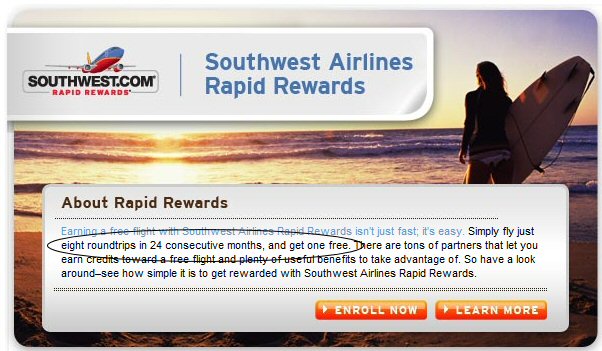

But for vegetarian activists, anybody taking on the vegetarian badge can be a positive, even if they fall short of the strict definition, says Ms Gellately, alluding to a virtual vegetarian escalator.

“People are moving along a pathway – the positive thing is that they see vegetarianism as aspirational.”

While activists might offer anecdotal evidence for trends like fish-eating vegetarianism, concrete numbers are not easy to come by.

There is a view that after a period of healthy growth in the 1990s, classic vegetarianism is now stagnant. It rose from 0.2% of the population during World War II to 1.8% in 1980, according to the consumer research company Mintel.

The firm’s most recent survey suggested 6% concurred with the statement “I am a vegetarian”. But the Food Standards Agency’s recent Public Attitudes to Food Issues survey found just 3% of the population was strictly vegetarian, and 5% partly vegetarian.

Viva cites a survey done on behalf of the Linda McCartney vegetarian food brand which suggested a figure of 10%.

Easy label

She was raised mostly as a vegetarian, but given fish for health reasons. She became an orthodox vegetarian at university but then returned to eating fish later. It’s now the only meat that she eats.

“I was brought up as a vegetarian. We were given the choice when we were young. It was all about animal rights and how animals were factory farmed. [My parents] told us the the reasons and we agreed with them.

“We were fed fish. It’s important for your brain to have oily fish [when young]. When I became a proper vegetarian I started to get quite ill and tired.”

Her objection is mainly to the way meat is produced, not to the idea of eating an animal. She uses the term “vegetarian” almost for the sake of convenience. If she is dining with people for the first time, it makes things simpler.

One of the reasons it’s so hard to assess the level of vegetarianism is because of the multiple definitions of the term.

It is clear, however, that meat-free and meat-substitute meals make up more and more of what we eat. The marketers and the activists are dealing with new groups of people, known as meat-avoiders and meat-reducers. Outside those who have a clear philosophical platform for eschewing meat, there are increasing numbers of these people, either cutting down on meat or trying not to eat it where possible, but without necessarily ever calling themselves “vegetarian”.

Mintel categorises 23% of the population as meat-reducers, people attempting to eat less meat, probably mainly for health reasons. Another factor of climate change – livestock rearing produces methane, which is 23 times more powerful than carbon dioxide. It identifies 10% as meat-avoiders, people who plan to eat little or no meat but sometimes lapse, and who might well accept the ethical basis of vegetarianism.

“More than a quarter of people say they eat less meat than they did five years ago. There is a shifting change in the diet,” says Ms Gellatley. “A third of our membership are meat reducers.”

Many people will start by giving up red meat for health reasons, then give up white meat, and so on. Despite initially doing it for non-ethical reasons, these people can then take on the philosophical mantle, says Ms Gellatley.

But despite the health messages about certain kinds of meat, and the arguments over the amount of energy it takes to produce meat, the vast majority in the UK still eat meat. And one-fifth, according to Mintel, like to have meat every day.

Posted in Advice, General Hypocrisy | 4 Comments »